New paradigm to predict behaviour of atmospheric rivers

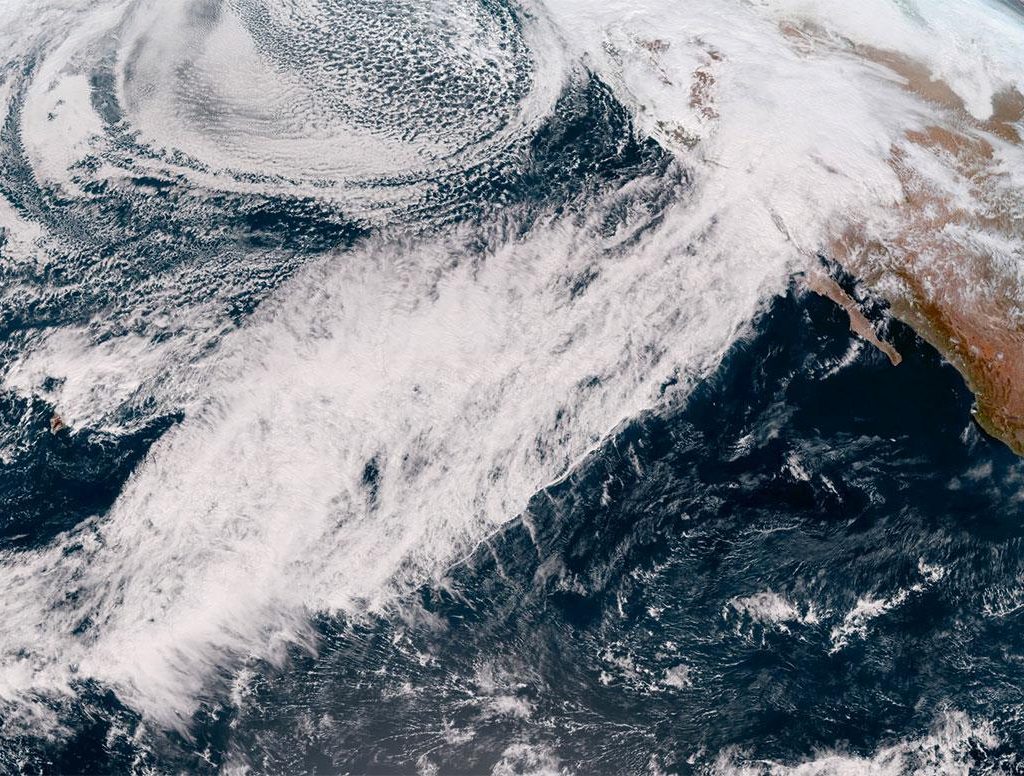

An atmospheric river carries moisture in a narrow, fast-moving band over the Pacific Ocean. A new equation by UChicago researchers explains the underlying processes behind these rivers and could help enhance future extreme weather predictions. Credit: NOAA

University of Chicago – Scientists at the University of Chicago developed an equation to better predict a type of weather phenomenon that brings extreme amounts of precipitation.

Da Yang, assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University of Chicago, and Hing Ong, a postdoctoral researcher at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Ill., described a new equation they developed to better understand the processes that drive atmospheric rivers.

Atmospheric rivers are long, narrow regions of concentrated water vapour accompanied by strong winds that carry moisture from the tropics toward the poles. They can transport as much as 15 times the amount of water that flows through the mouth of the Mississippi River, and they can bring heavy rain, snow, and strong winds. Up to half of California’s annual precipitation is brought by atmospheric rivers.

They are an essential element of the global climate, and understanding them will help improve the ability to forecast weather, manage water resources, and predict flood risk.

Atmospheric rivers are monitored using integrated vapour transport (IVT), which describes the amount and velocity of water vapour moving through the atmosphere. This metric is enough to develop tracking and monitoring algorithms, but to address fundamental questions about the evolution of atmospheric rivers, scientists need a governing equation. This is a mathematical expression that describes how a system changes based on specific rules or principles.

A governing equation would let scientists ask big-picture questions, Yang said, such as, “What provides energy to form and sustain atmospheric rivers? And why do they move eastward?”

His team found that atmospheric rivers mainly increase in strength because potential energy converts into kinetic energy.

Yang and Ong hope the new framework will enhance the accuracy of atmospheric river predictions, especially for extreme weather events and in the context of a changing climate. Using this new framework, Yang’s team found that atmospheric rivers mainly increase in strength because potential energy converts into kinetic energy. The rivers weaken due to condensation and turbulence and travel eastward due to the horizontal movement of kinetic energy and moisture by air currents.

“(The new equation has) the added benefit of being an intuitive first principle-based governing equation,” Yang said, “That can tell us what makes an atmospheric river stronger, what dissipates it, and what makes it propagate eastward—in real-time.”

“We know that with climate change, the amount of water vapour is increasing,” Yang added. “Under the assumption that the circulation doesn’t change much, you may expect that the individual atmospheric river may get stronger.”