NASA study: crops, forests responding to changing rainfall patterns

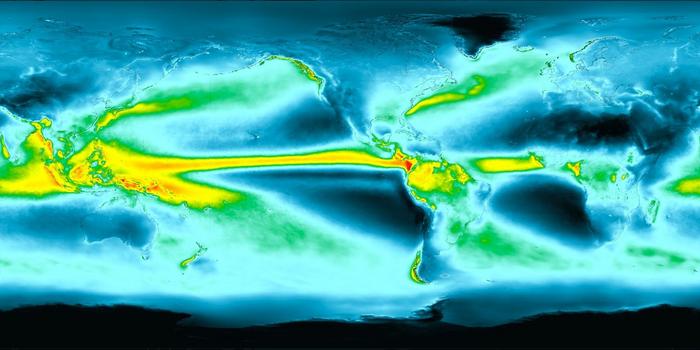

Earth’s rainy days are changing and plant life is responding. This visualization shows average precipitation for the entire globe based on more than 20 years of data from 2000 to 2023. Cooler colors indicate areas that receive less rain. Warm colors receive more rain. (NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio)

By Sally Younger, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

(WeatherFarm) – A new study led by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration found that how rain falls in a given year is nearly as important to the world’s vegetation as how much. Researchers showed that even in years with similar rainfall totals, plants fared differently when that water came in fewer, bigger bursts.

In years with less frequent but more concentrated rainfall, plants in drier environments such as the United States Southwest were more likely to thrive. In humid ecosystems like the Central American rainforest, vegetation tended to fare worse, possibly because it could not tolerate the longer dry spells.

Scientists have previously estimated that almost half of the world’s vegetation is driven primarily by how much rain falls in a year. Less well understood is the role of day-to-day variability, said NASA scientist Andrew Feldman. Shifting precipitation patterns are producing stronger rainstorms — with longer dry spells in between — compared to a century ago.

“You can think of it like this: if you have a house plant, what happens if you give it a full pitcher of water on Sunday versus a third of a pitcher on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday?” said Feldman. Scale that to the size of the U.S. Corn Belt or a rainforest and the answer could have implications for crop yields and ultimately how much carbon dioxide plants remove from the atmosphere.

Researchers analyzed two decades of field and satellite observations, spanning millions of square miles. Their study area encompassed diverse landscapes from Siberia to the southern tip of Patagonia.

They found that plants across 42 per cent of Earth’s vegetated land surface were sensitive to daily rainfall variability. Of those, a little over half fared better — often showing increased growth — in years with fewer but more intense wet days. These include croplands as well as drier landscapes like grasslands and deserts.

In contrast, broadleaf forests and rainforests in lower and middle latitudes tended to fare worse under those conditions. The effect was especially pronounced in Indo-Pacific rainforests, including in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Statistically, daily rainfall variability was nearly as important as annual rainfall totals in driving growth worldwide.

The new study relied primarily on a suite of NASA missions and datasets, including the Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) algorithm, which provided rain and snowfall rates for most of the planet every 30 minutes using a network of international satellites.