International lessons in child farm safety

| 4 min read

Jessie Adams presents at the virtual CASA conference Oct. 6.Jessie Adams shared lessons from her PhD research on child farm safety and what must be done to create a culture of safety at the recent CASA conference. Photo: Screengrab from Jessie Adams presentation.

Keeping kids safe on the farm may require long-term cultural changes and cross-industry collaboration.

That was the message from Jessie Adams at the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association (CASA) conference last month. Adams, who is with the National Centre for Farmer Health in Australia, presented her PhD research on child farm safety and how its lessons may be applicable in Canada as well as Australia.

Though numbers of farm deaths in Canada are improving, the numbers are still concerning, including among children. According to Canadian Occupational Safety, there were 26 deaths of children on farms in the decade preceding 2023.

In Australia, Adams said 248 children have lost their lives on farms since 2001. In 2024, children represented around 15 per cent of serious farm injuries in Australia overall.

“The results of my research highlighted that there is a need for change in some farm safety behaviours and attitudes in Australian farming,” said Adams. “Achieving this requires a cultural shift, which we know is a very long-term goal, rather than something that will be happening overnight.”

For this research, she developed a survey along with a panel of experts on hazards and risk behaviours, for children aged five to 14 and their parents. In total, 107 parents and 62 children responded.

Dual purpose space

Several challenges in child farm safety arise from the blurring of lines between home and workplace on farms. Adams said 99 per cent of parents reported their child was allowed to work on the farm site, and over 80 per cent said they take their children with them when doing farm work.

“This shows that a farm is not just a workplace, but it’s a child’s home and playground, a place where they are cared for while work is being done.”

Only two per cent of parents considered the legal requirements of the farm as a worksite, however. Adams said it is unclear “if this reflects a lack of awareness that it is a work site, there are considerations or cultural attitudes towards workplace regulations.”

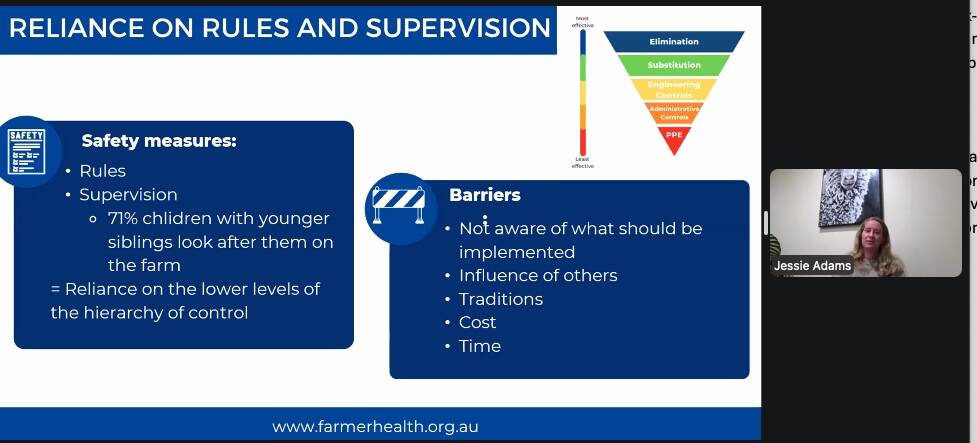

The main hazards for children on farms included bodies of water and horses, but Adams said small vehicles like side-by-sides and ATVs are also very hazardous. Though children under 16 are widely advised not to ride or operate ATVs, Adams’ research showed over half of children rode as passengers and almost two thirds of children said they operated ATVs without parental supervision. Only half wore helmets.

This, coupled with the fact that parents said they see themselves as role models (90 per cent of respondents) and the acknowledgement by one-third of parents that they sometimes work in a way they do not want their child to copy, such as rushing jobs or not using proper PPE, shows the further potential for child accidents or fatalities on farms.

As part of her research, Adams completed a six-week fellowship which took her to Ireland, the U.S. and Canada, where she met with local agricultural safety groups to learn what lessons she could bring back to Australia.

“During the fellowship, I was lucky enough to observe a variety of child farm safety education programs. They were all unique, but highlighted the need to make sure they’re engaging, age-appropriate and continuous.”

Embracing safety culture

To achieve an environment of farm safety for children, Adams said a community-wide culture of safety is key.

“Farm safety isn’t the role of one organization,” she said. “When everyone sees themselves as part of the solution, from families to schools to industries, the impact is greater, and peer influence can be a powerful driver for change.”

These types of collaborations can expand a message’s reach.

Funding may be a challenge, and Adams recommended engaging with agricultural groups as partners, not just funders, and advocating for child farm safety as a national priority.

“A key strategy is to communicate the shared benefits,” she said. “Improving safety protects children and families, but it also strengthens the industry’s reputation, reduces workplace risk and supports a sustainable rural workforce.”

She also suggested integrating safety into school curriculums and using stories, visuals and real-life examples to connect with children.

“Teaching must be creative, interactive, relevant and story based,” said Adams.

Other key points included introducing education earlier to make it more likely messages will evolve into lifelong habits, the need for practical, hands-on learning and reaching out to educate all groups, not only farm kids.