‘Ghost fleas’ cause mercury to rise, literally

We hear a lot about how mercury, as a byproduct of burning coal, makes its way from the atmosphere into waterways and, eventually, certain fish we eat — but a weird little culprit may be causing unexpectedly high mercury levels in fish from at least one Prairie lake.

Researchers at the University of Regina, studying Katepwa Lake in southern Saskatchewan’s Qu’appelle Valley, have found a translucent type of water flea — which they’ve dubbed “ghost fleas” — are dredging up mercury-filled sediment from the lake bottom, bringing higher levels of it into the diets of fish in the lake.

A lot of environmental mercury comes from combustion of coal — not to mention natural sources, such as volcanoes and geothermal springs — and can be carried over long distances in the air.

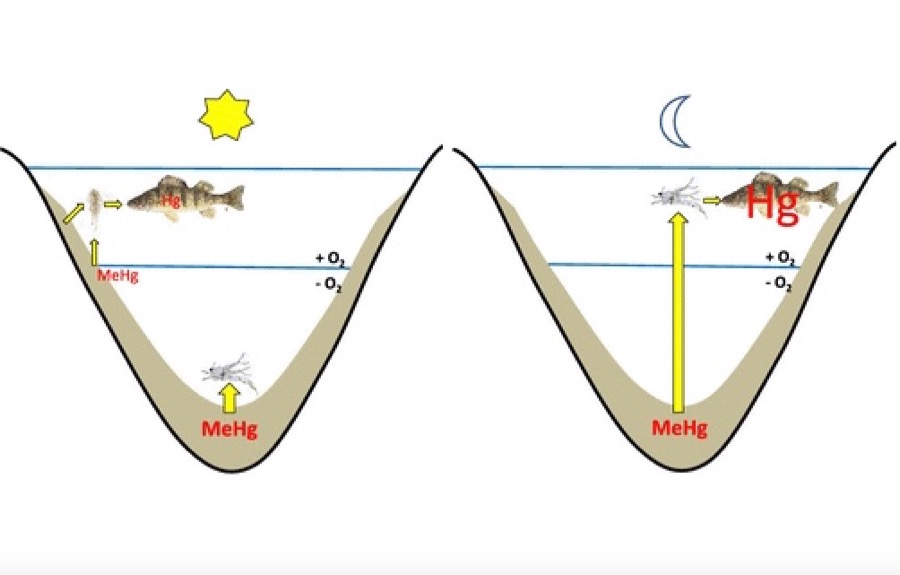

Inorganic mercury isn’t considered a health risk by itself, but in the presence of certain bacteria and absence of oxygen, it produces methylmercury, which is both a neurotoxin and the type of mercury found most often in fish.

Neurotoxins can permanently damage brain activity in humans — with infants who are breastfed, young children and pregnant women at particular risk.

Katepwa, like other Prairie lakes, is considered “productive,” meaning it’s got nutrients that allow algae to grow, which usually dilute methylmercury concentrations and reduce the levels seen in those lakes’ fish, according to U of R biologist Dr. Britt Hall.

“But in Katepwa Lake, the data was showing that methylmercury concentrations are actually quite high, and we didn’t know why that was,” she said in a release.

“Fisheries in highly productive prairie lakes of Canada and the United States frequently have fish consumption advisories due to elevated mercury concentrations,” the researchers wrote in a recent paper in Environmental Science + Technology Letters of the American Chemical Society.

That’s unexpected, they wrote, because “such alkaline lakes often exhibit lower methylmercury concentrations in basal trophic levels than those expected in less productive basins with circumneutral pH.”

The U of R study suggests that at Katepwa, the methylmercury could be coming from Leptodora kindtii, a relatively large (1.5-cm) but colourless water flea.

The adult “ghost fleas” migrate up from mercury-rich sediments at the lake bottom — at night — to feed near the surface of the water. Fish can’t see the ghost fleas, but a separate study has shown fish can sense pressure waves the ghost fleas make when they swim.

Thus the fleas act like a “mercury elevator,” bringing methylmercury up to the fish that feed on them.

“This migration to the surface increases the amount of toxin in the fish, which are in turn eaten by larger and larger fish, resulting in a bioaccumulation of mercury in the top predator — us,” U of R limnology professor Dr. Peter Leavitt said in the same release.

“The important message to fisheries managers is that productive lakes in the Prairies may have high levels of methylmercury, which does not fit our expectations. Knowing this can help people reduce the risk of mercury poisoning,” Hall said.

“Managers can use this information to produce consumption advisories to warn sports fishers about how much fish they should be eating from the lakes.”