Himalayan glaciers keep themselves cool: study

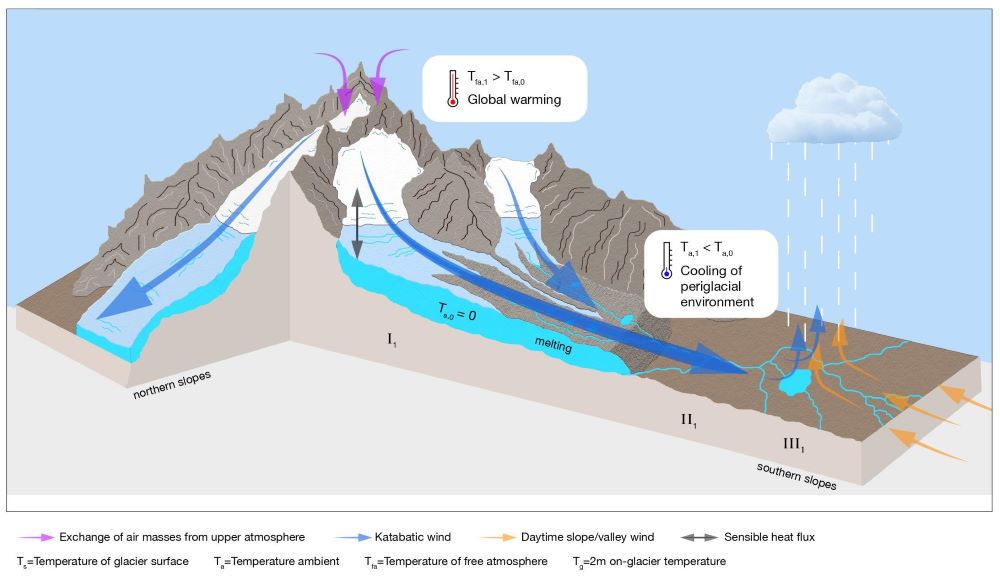

Schematic diagram of the air cooling in the surroundings of Himalayan glaciers. © Salerno / Guyennon / Pellicciotti / Nature Geoscience

ISTA – An international team of researchers co-led by Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) Professor Francesca Pellicciotti revealed a stunning phenomenon: rising global temperatures have led Himalayan glaciers to increasingly cool the air in contact with the ice surface. The ensuing cold winds might help cool the glaciers and preserve the surrounding ecosystems. The results, found across the Himalayan range, were published in Nature Geoscience.

Previously, scientists documented an elevation-dependent warming effect: they showed that mountain tops “felt” the effect of global warming stronger and warmed up faster. Yet, a high-altitude climate station at the base of Mount Everest in Nepal showed an unexpected phenomenon: the measured surface air temperature averages remained suspiciously stable instead of increasing.

The Pyramid International Laboratory/Observatory climate station, located at a glacierized elevation (5,050 metres) on the southern slopes of Mount Everest, alongside the Khumbu and Lobuche glaciers, has continuously recorded hourly meteorological data for nearly three decades. Now, an international team of researchers led by Pellicciotti and National Research Council of Italy (CNR) researchers Franco Salerno and Nicolas Guyennon cracked the code. The warming climate has triggered a cooling reaction in the glaciers: it is causing cold winds—katabatic winds—to flow down the slopes.

To explain the observed phenomenon, the team had to examine the data thoroughly.

“We found that the overall temperature averages seemed stable for a simple reason. While the minimum temperatures have been steadily on the rise, the surface temperature maxima in summer were consistently dropping,” Salerno said.

The glaciers are reacting to the warming climate by increasing their temperature exchange with the surface, Pellicciotti explained. Global warming causes an increased temperature difference between the warmer environmental air over the glacier and the air mass in direct contact with the glacier’s surface.

“This leads to an increase in turbulent heat exchange at the glacier’s surface and stronger cooling of the surface air mass,” Pellicciotti said.

As a result, the cool and dry surface air masses become denser and flow down the slopes into the valleys, cooling the lower parts of the glaciers and the surrounding ecosystems.

“This phenomenon is the outcome of 30 years of steadily increasing global temperatures. The next step is to find out which key glacier characteristics favor such a reaction,” Pellicciotti added. “While other glaciers are experiencing dramatic changes right now, the glaciers in High-Mountain Asia—the Third Pole—are very large, hold more ice masses, and have longer response times. Thus, we might still have a chance to ‘save’ these glaciers.”

Thus, Pellicciotti and her team will soon investigate whether the world’s only stable or growing glaciers in the Pamir and Karakoram mountains, to the north-west of the Himalayas, are also reacting to global warming by blowing cold winds down their slopes.

“The slopes of the Pamir and Karakoram glaciers are generally flatter than in the Himalayas. Thus, we hypothesize that the cold winds might act to cool the glaciers themselves rather than reaching lower down into the surrounding environments. We will be able to tell in the next couple of years,” she added.

“We believe that the katabatic winds are the response of healthy glaciers to rising global temperatures and that this phenomenon could help preserve the permafrost and surrounding vegetation,” Guyennon said.

Does this mean that the glaciers are approaching their preservation tipping point? “They are in some places, but we do not know where and how,” Pellicciotti answered. Yet, she does not lose heart easily: “Even if the glaciers can’t preserve themselves forever, they might still preserve the environment around them for some time. Thus, we call for more multidisciplinary research approaches to converge efforts toward explaining the effects of global warming,” she concluded. These efforts could prove instrumental in changing the course of human-caused climate change.