Scientists turn plant waste into jet fuel

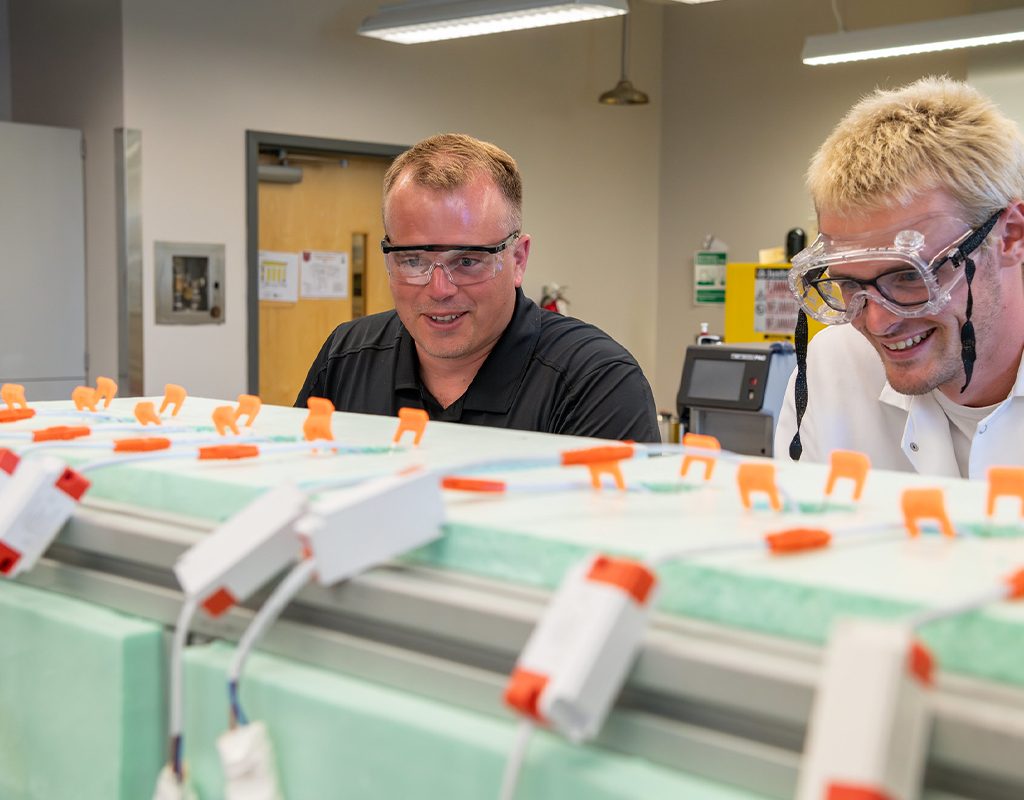

Joshua Heyne, director of the WSU Bioproducts, Sciences, and Engineering Laboratory, and research assistant Conor Faulhaber, examine swelling results from a material compatibility test related to sustainable fuels. (Washington State University)

Washington State University — Washington State University (WSU) scientists successfully tested a new way to produce sustainable jet fuel from lignin-based agricultural waste.

The team’s research demonstrated a continuous process that directly converts lignin polymers, one of the chief components of plant cells, into a form of jet fuel that could help improve the performance of sustainably produced aviation fuels.

“Our achievement takes this technology one step closer to real-world use by providing data that lets us better gauge its feasibility for commercial aviation,” said Bin Yang, professor in WSU’s Department of Biological Systems Engineering.

Lignin is derived from corn stover — the stalks, cobs and leaves left after harvest — and other agricultural byproducts.

The team developed a process called “simultaneous depolymerization and hydrodeoxygenation,” which breaks down the lignin polymer and at the same time removes oxygen to create lignin-based jet fuel.

Global consumption of aviation fuel reached an all-time high of nearly 100 billion gallons in 2019, and demand is expected to increase in the coming decades. Sustainable aviation fuels derived from plant-based biomass could help minimize aviation’s carbon footprint, reduce contrails and meet international carbon neutrality goals.

This research marked the team’s first successful test of a continuous process, which is more feasible for commercial production.

“The aviation enterprise is looking to generate 100 per cent renewable aviation fuel,” said Josh Heyne, co-director of the WSU-Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Bioproducts Institute. “Lignin-based jet fuel complements existing technologies by, for example, increasing the density of fuel blends. We’re working to create an effective, commercially relevant technology for a complementary blend component that can achieve the 100 per cent drop-in goal.”

The team is now working to refine their process for better efficiency and reduced costs.