Tackling both hunger and food-related emissions may take trade-offs

Securing healthy diets worldwide isn’t going to reduce greenhouse gas emissions everywhere, and not all diets tailored to limit emissions are going to improve health outcomes for everyone, so it may take trade-offs to accomplish both goals, a new report suggests.

Securing healthy diets worldwide isn’t going to reduce greenhouse gas emissions everywhere, and not all diets tailored to limit emissions are going to improve health outcomes for everyone, so it may take trade-offs to accomplish both goals, a new report suggests.

The 2020 edition of The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, released July 13 by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), includes an analysis of some different diets for their environmental benefit while also looking at the environmental impact of rescuing people from hunger and malnutrition.

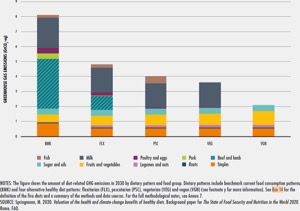

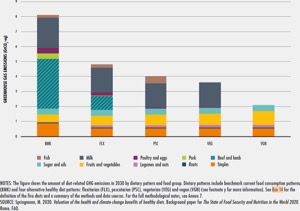

It’s estimated that during the period from 2007 through 2016 period, the system underpinning current food consumption patterns worldwide was responsible for 21 and 37 per cent of total human-caused greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Food system emissions include both carbon dioxide and non-CO2 gases coming from on-farm crop and livestock activities; related land use and land-use change dynamics; and food processing, retail and consumption patterns — which include food loss and waste as well as the emissions generated producing chemical fertilizers and fuel.

“Data limitations” make it tough to measure and compare other sustainability markers country-by-country worldwide, the report said, when considering other environmental impacts related to land use, energy and water use.

FAO has previously estimated that the world will need to produce about 50 per cent more food by 2050 to feed a growing world population, assuming no changes in food loss and food waste levels. If dietary patterns and food systems remain the way they are now, that would mean “significant increases in GHG emissions” and other environmental impacts, the report said.

When we look at countries’ national food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs), they’re often pretty similar — limiting calories, trans and saturated fats, sugars and salt, while raising consumption of plant-based foods including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds.

“Healthy diets present important opportunities for reducing GHG emissions in some contexts, because they are rich in plant-based foods that emit lower GHG levels compared with diets that are heavy in red meat consumption,” the report said.

“However, this may not be the best option in order to pursue a reduction in GHG emissions, especially in contexts where consumption of red meat and dairy can provide valuable sources of essential nutrients to vulnerable populations, particularly to prevent undernutrition.”

There’s no single “exact make-up” of a diet that’s both healthy and sustainable, the report says, but the guiding principles for a healthy diet are the same — one such principle being that a healthy diet can contain animal-source foods in “moderate to small” amounts.

“Specifically, a healthy diet can include moderate amounts of eggs, dairy, poultry, fish and small amounts of red meat,” the report said. “This principle, based on health considerations, also presents an opportunity for countries to make the shift to healthy diets and simultaneously contribute to reductions in GHG emissions.”

In other words, “not all healthy diets are sustainable and not all diets designed for sustainability are always healthy or adequate for all population groups,” the report said. “This important nuance is not well understood and is often missing from ongoing discussions and debates on the potential contribution of healthy diets to environmental sustainability.”

Variations across subregions and countries show the “potential trade-offs” that need to be managed as countries transform food systems toward healthy diets that also include sustainability considerations, the report said.

“For example, countries with high burdens of undernourishment and multiple forms of malnutrition might see their consumption-related emissions rise as growing shares of their population consume healthy and nutrient-adequate diets.

“In these cases, fighting hunger and malnutrition by increasing the diversity of nutritious foods available for infants and young children outweighs the negative effects deriving from higher national GHG emissions.”

A study of 140 countries gauging the GHG emissions of nine “increasingly plant-forward” diets showed several countries would need to increase their per-capita GHG footprint to meet energy needs and the recommended protein intake for a health diet.

Uganda, for example, would need to raise its per-capita GHG footprint to meet energy needs and boost recommended protein intake of at least 12 per cent of energy needs.

Meanwhile, if dietary energy levels are reduced, even while maintaining the same minimum 12 per cent energy from protein, GHG footprints could be reduced in countries including Canada and the U.S., where current diets exceed energy needs.

In short, a shift to healthy diets “would bring about significant reductions in both individual health costs and global carbon footprint by 2030, compared with current dietary patterns,” the report said.

“However, given that not all healthy diets are sustainable and not all diets designed for sustainability are always healthy for everyone, the nature of this shift needs to be decided carefully.”