Water levels break historical records

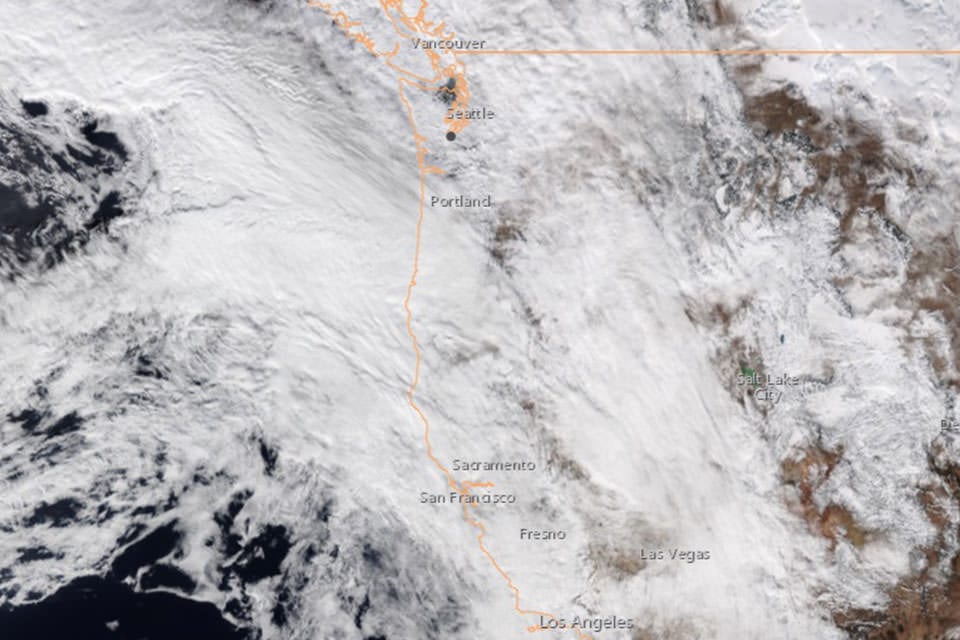

A winter storm as seen from NOAA's GOES satellite on December 29, 2022, in the Pacific Northwest. The storm coincided with higher than normal high tides, resulting in high tide flooding across Washington. Credit: NOAA

NOAA – December was an active month for NOAA’s National Water Level Observation Network (NWLON). A staggering eight stations observed all-time high water levels — some of which broke records in place for 40 years. The Pacific Northwest was the most affected region, with four locations in the state of Washington observing its highest-ever water levels on record.

Friday Harbor station: Water levels reached 3.60 feet above Mean Higher High Water (MHHW). This station’s previous record was 3.38 ft above MHHW, set on Dec. 16, 1982. Station records go back to 1934.

Seattle station: Water levels reached 3.76 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 3.16 ft, set on Jan. 7, 2022. Station records go back to 1899.

Tacoma station: Water levels reached 3.90 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 3.27 ft, set on Jan. 7, 2022. Station records go back to 1997.

Port Townsend: Water levels reached 3.54 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 3.08 ft, set on Dec. 16, 1982. Station records go back to 1972.

In addition to Washington’s stations, new water level records were set at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, and two water level stations in Alaska: Sand Point and King Cove.

Quonset Pointstation: Water levels reached 3.72 ft (1.13m) above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 3.22 ft above MHHW, set on Apr. 16, 2007. Station records go back to 1999.

Sand Point station: Water levels reached 4.68 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 4.25 ft above MHHW, set on Dec. 31, 1986. Station records go back to 1972.

King Cove station: Water levels reached 4.98 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 4.29 ft, set on Jan. 30, 2007. Station records go back to 1917.

Nikolski, Alaska station: Water levels reached 2.82 ft above MHHW. This station’s previous record was 2.54 ft, set on Jan. 9, 2021. Station records go back to 2006.

High tide flooding happens when higher than normal high tides, such as a perigean spring tide, combine with sea level rise and, in some areas, coastal subsidence. While coastal flooding does not always occur during a perigean spring tide, it can increase the likelihood of minor high tide flooding in low-lying areas. This type of flooding, frequently seen during high tide and extreme weather events, exceeds established flood impact thresholds. Even minor high tide flooding events can result in inundated roads and backed up sewers. Weather conditions often compound this flooding, which can cause even more damage. This happened on Dec. 27, 2022, when a strong winter storm hit the Pacific Northwest while tides were still above normal following the perigean spring tide.

Every three months, NOAA releases its High Tide Bulletin. This seasonal publication predicts when coastal regions of the U.S. will experience higher than normal high tides. The bulletin alerts coastal communities to periods of extreme tidal fluctuation and is part of a suite of tools designed to lessen the effects of high tide flooding.

In 2023, NOAA plans to unveil a new model to more accurately predict when and where high tide flooding will likely occur up to a year ahead of time. This represents a major advancement in the agency’s seasonal high tide flooding predictions.

NOAA predicts many coastal regions of the U.S. will experience higher than normal high tides between January and February 2023. The U.S. West Coast, in particular, may experience some of the highest tides between Jan. 18 to 26 and Feb. 18 to 21. These dates coincide with a perigean spring tide.

Predictions from last year’s Sea Level Rise Technical Report show that high tide flooding will become more common and more severe over the coming decades. As sea levels continue to rise, conditions that cause minor and moderate high tide flooding today will cause moderate and major high tide flooding by 2050. For example, the NOAA tide station at Seattle can expect to see its high tide flooding days more than double between 2030 and 2050, increasing from four days a year to nine days a year.