World glaciers hold less ice than thought: survey

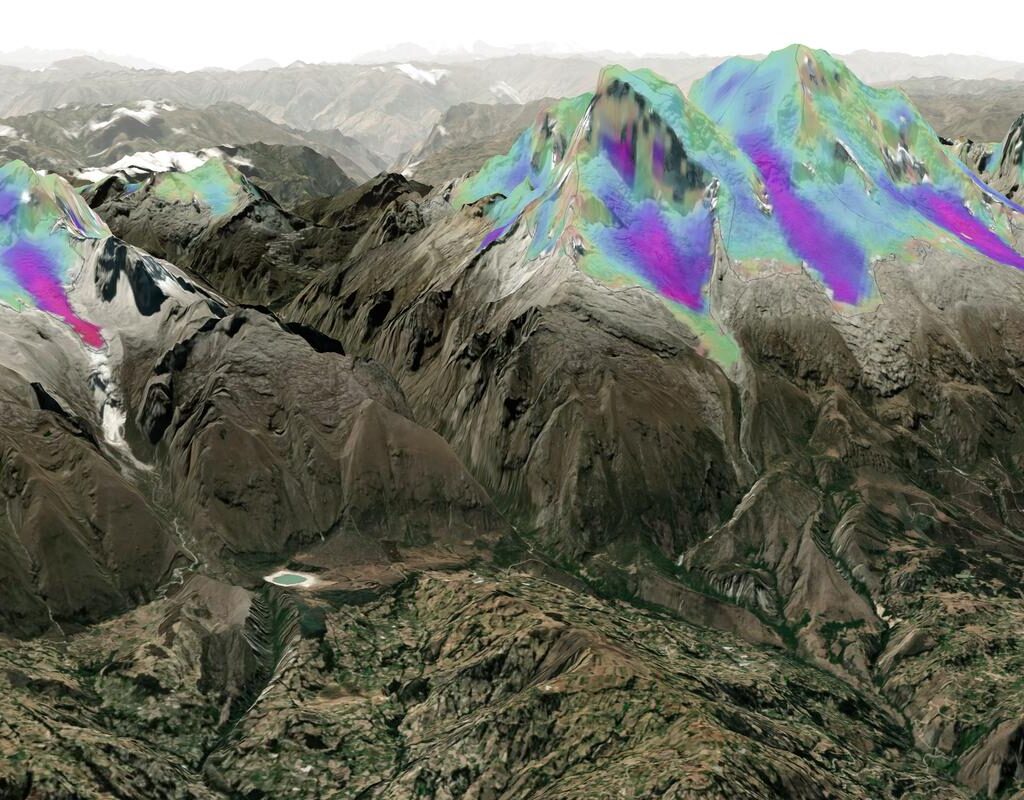

Dartmouth College – The amount of freshwater trapped in glaciers around the world may not be as large as previously thought, according to a new survey conducted by researchers from the Institute of Environmental Geosciences (IGE) and Dartmouth College that measured the depth and velocity of more than 250,000 mountain glaciers.

Published in the journal Nature Geosciences, the new research suggests that there is 20 per cent less ice available for sea level rise in the world’s glaciers than had been thought. While the overall trend was clear, the data was mixed, with some areas seeing more ice that had been previously thought.

The results have implications on the availability of water for drinking, power generation, agriculture and other uses worldwide. The findings also change projections for climate-driven sea level rise expected to affect populations around the globe.

“Finding how much ice is stored in glaciers is a key step to anticipate the effects of climate change on society,” said Romain Millan, a postdoctoral scholar at IGE and lead author of the study. “With this information, we will be closer to knowing the size of the biggest glacial water reservoirs and also to consider how to respond to a world with less glaciers.”

“The finding of less ice is important and will have implications for millions of people around the world,” said Mathieu Morlighem, the Evans Family Professor of Earth Sciences at Dartmouth and co-author of the study. “Even with this research, however, we still don’t have a perfect picture of how much water is really locked away in these glaciers”

The new atlas covers 98 per cent of the world’s glaciers. According to the study, many of these glaciers are shallower than estimated in prior research. Double counting of glaciers along the peripheries of Greenland and Antarctica also clouded previous data sets.

The study found less ice in some regions and more ice in others, with the overall result that there is less glacial ice worldwide than previously thought.

The research found that there is nearly a quarter less glacial ice in South America’s tropical Andes mountains. The finding means that there is up to 23 per cent less freshwater stored in an area from which millions of people depend during their everyday lives. The reduction of this amount of freshwater is the equivalent of the complete drying of Mono Lake, California’s third largest lake.

On the contrary, Asia’s Himalayan mountains were found to have over one-third more ice than previous estimates. The result suggests that about 37 per cent more water resources could be available in the region, although the continent’s glaciers are melting quickly.

“The overall trend of warming and mass loss remains unchanged. This study provides the necessary picture for models to offer more reliable projections of how much time these glaciers have left,” said Morlighem.

The melting of glaciers due to climate change is one of the main causes of rising sea levels. It is currently estimated that glaciers contribute 25-30 per cent to overall sea level rise, threatening about 10 per cent of the world’s population living lower than 30 feet above sea level.

The reduction by 20 per cent of glacial ice available for sea level rise lessens the potential for glacial contribution to sea level by three inches, revising it downward from 13 inches to just over 10 inches. This projection includes contributions from all the world’s glaciers except the two large ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, which have a much larger potential contribution to sea level rise.

“Comparing global differences with previous estimates is just one side of the picture,” said Millan. “If you start looking locally, then the changes are even larger. To correctly project the future evolution of glaciers, capturing fine details is much more important than just the total volume.”

According to the study, depth measurements previously existed for only about one per cent of the world’s glaciers, with most of those glaciers only being partially studied.